Ain’t What It Used to Be

-

The availability of goods and services has been hampered by higher than anticipated demand following a complete shutdown.

-

Inflation has emerged as the economy attempts to allocate scarce resources.

-

We believe that the inflationary pressures from shipping and manufacturing schedules will fade. Housing and wages could be more persistent.

-

Capital markets have taken inflation pressures and the probable Fed reaction in stride. We believe moderately higher inflation will benefit many companies’ earnings after an extended period with very little pricing power.

Throughout the time warp of the Coronavirus pandemic, I think everybody has looked forward to things returning to “normal”. They’re not. That trip I looked forward to taking began and ended with flights that felt more like a hospital visit or detention at school than the leisurely experience of old. There were 10,000 people and a water fountain in each airport. Once I got there, the rental car was absurdly expensive if available at all. Restaurants are pretty much high dollar chaos in most cases due to labor shortages. I can’t go visit sick loved ones in the hospital and there are legitimate concerns that fatigue and shortages might limit the level of care they receive. I turn on the news and then turn it off because the takeaway is always the same: We’re not getting along very well. Traffic is out of control. House prices are through the roof. Might as well sit on the porch I’ve got and reminisce about the good old days. Ain’t what it used to be.

Now that I’ve got all that off my chest, I’ll live in the here and now as we all must do. It seems to all boil down to two things. We have a lot of demand, which is good. We don’t have much supply, which is bad. The outcome is that it is hard to get what you want and expensive when you do. A bit of a first world problem, but worth investigating.

We’ll start with the bad. Our take is that we are experiencing a form of economic atrophy. In March 2020, we brought a large and sophisticated economy to a screeching halt. Production stopped; orders were canceled; people quit using services; many people stopped working. Our economy was intricate and refined when running at full speed. We did not have much safety stock because efficient supply chains and just in time production schedules could simply replace what was sold. Service providers offered efficient and low-cost service because they were loaded with people who were trained to solve the small problems that led to big incremental benefits over time. We were a well-oiled machine. When those folks walked out the door they took a lot of “know-how” with them. When the supply chain and production stopped, it was complicated to reload them in an environment of much higher than anticipated demand.

Where did everybody go?

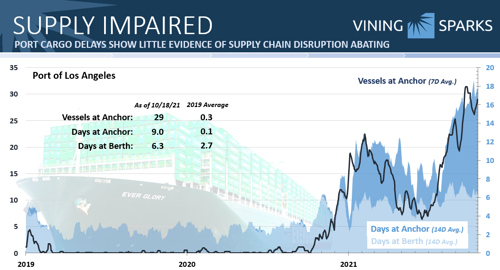

The most immediate fallout from the atrophy is inflation. We don’t know whether it is “transitory” or enduring. The problem with inflation is that it compounds, just like interest. If these are temporarily high readings, there won’t be any problem. If it persists, the purchasing power of savings will fall; Interest rates will rise; and the demands for wages that keep up with higher prices will drive still higher prices. In our view, the cost of “things” is a blip that might take 6 months to a year to resolve. Supply chains are stressed due to port congestion, price and access for shipping containers and capacity of trucks and trains to haul things off the port to warehouses (see chart). In general, we believe the availability and cost of shipping will moderate due to competition and adequate underlying capacity.

Sources: Port of Los Angeles, Vining Sparks

The cost of labor and housing are concerns. People have moved. People have retired. People have saved, providing flexibility around reentering the workforce. Many employees that remain seem beleaguered. Some are quitting. We don’t know the precise balance of factors, but increasingly generous employment offers are not drawing much needed labor back to work, despite the expiration of most of the supplemental relief available under The American Rescue Plan of 2021. Unfortunately, we don’t have a clearing price for bringing people back to work or know what that price will do to the price of a hamburger or the quality of a hospital visit.

Where did all these people come from?

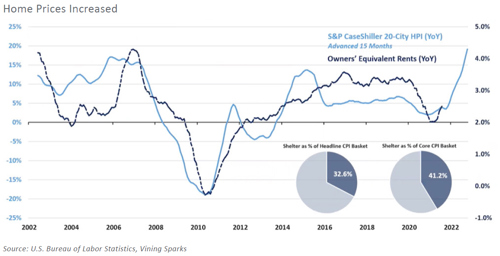

Housing is more complicated. High levels of unemployment and a slower than anticipated recovery do not seem to foot with a housing boom, but we are seeing one. Home prices increased 15% year-over-year in July and 20% in August (See chart). For the Consumer Price Index (CPI) calculation, home prices are normalized using a calculation called Owners’ Equivalent Rents. The calculation creates a lag between the price of buying an existing home and when higher prices show up in CPI. Current price trends ultimately will show up in CPI with some natural moderation inherent in the calculation. Shelter is a large component of CPI, so the longer the monthly house price readings remain at these levels, the more pronounced the impact on inflation. Labor comes into play here as well because the pressure valve is new homes, which are not keeping up with demand. Over the intermediate and long term, housing demand and population growth should have a strong relationship, but they don’t right now.

Explaining things does about as much good as sitting on the porch daydreaming about the past. Most concerns about inflation reflect real life experiences in the 1970’s and early 1980’s. “Stagflation” is a word nobody wants to hear again as very high rates of inflation and high unemployment drove a pronounced decline in standards of living. Without too many specific comparisons, we don’t think we are looking at “Stagflation” again. First, we believe economic growth is likely to continue in the absence of further Covid flare-ups. There is plenty of demand and we believe any shortfalls to current GDP are simply deferred at this point. Second, we believe the factors that have held down core inflation for the past 11 years remain in place: aging populations, technology and globalization. Finally, the objective data are not forecasting higher rates of inflation. The yield on a 10-year treasury remains low at 1.64% despite being off the lows set when the delta variant raised the greatest concern about growth. The breakeven for Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) at the 10-year maturing has risen to 2.62% from 2.28% on September 22. While this is a significant increase, it is far from extrapolating recent inflation readings above 4%. We do not see slightly higher inflation expectations as alarming. The TIPS breakeven is a proxy for investors’ inflation expectation.

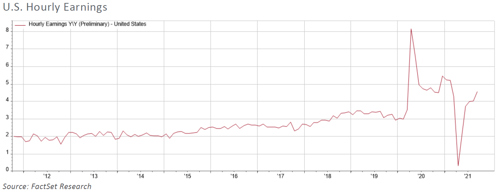

We think it is best to assume that there is a higher level of inflation in the future, but a manageable one based on current information. The Fed has wanted a higher level of inflation to meet goals for full employment, broadly defined. Wage growth drives higher prices, but also supports a higher standard of living provided the economy is growing. Average hourly earnings grew 4.6% year over year in September compared to an average increase of about 3.27% from August 2018 through March of 2020 and an average of 2.28% from 2011 through 2018.

The Federal Reserve believes it is time to start removing stimulus, which will also create a headwind for inflation. While curbing demand intuitively seems like a bad thing, “excess demand” created by easy money can create imbalances. While supply is the biggest imbalance in our opinions, demand is probably out of balance with sustainable levels at this point. At the September meeting, the Governors signaled that they are ready to start tapering the quantitative easing program implemented in response to the Covid crisis. The plan is to reduce purchases of treasuries gradually starting in November or December. The Fed’s desire to remove quantitative easing reflect not only concerns about inflation, but also a belief that healthy demand is sustainable without it. So far, both the bond market and the stock market have taken the probable removal of quantitative easing in stride.

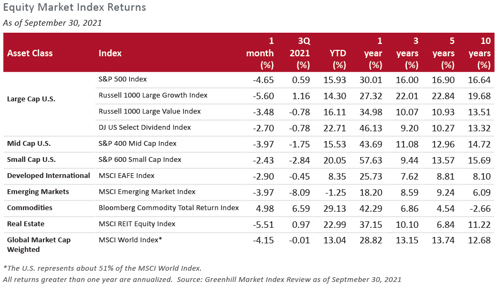

Equities saw a small decline in September, but the S&P 500 has delivered a 15.93% return year-to-date. The price-to-earnings multiple for the S&P 500 has declined as earnings have outstripped high expectations and many companies forecast continued growth. The S&P 500 price-earnings multiple for the next 12 months is 21.06. Forecast growth for S&P 500 earnings is 46% for 2021 and 9% for 2022. Absent a recession, both seem reasonable.

In some ways, inflation could be a benefit to stocks. As analysts, we were taught early on that there are 3 revenue drivers: volume, price and mix (ie going upmarket). Of these, pricing tends to be the most powerful for mature industries. Most participants in the US economy have had little pricing power since the global financial crisis. But this is changing, helped by strong demand. Costs will be higher too, but history suggests that productivity driven by technology and “know-how” can continue to drive profitability. For the entire economy, productivity is the pressure valve that relieves inflationary pressures. After years of modest productivity, recent readings have been stronger.

We believe growth will continue and inflation will be manageable. In this environment, we believe equities remain the best means of delivering returns beyond the rate of inflation. People will go back to work and restart the processes that deliver the goods and services we enjoy in a timely and affordable way. While it ain’t what it used to be, we believe it will be same as it ever was.