Will the Frugal Fund the Fix?

What if we could fix the Social Security deficit right now with no legislation and no new taxes? What if we could accomplish that with no benefit cuts that would push any senior into poverty? Turns out we can and perhaps we will. But there is no “free lunch.” The fix requires benefits to be capped at $2,050 per month, meaning a cut of almost 50% for high income seniors, the people who have paid the most into the program and who already, through current program structure, significantly subsidize lower income participants.

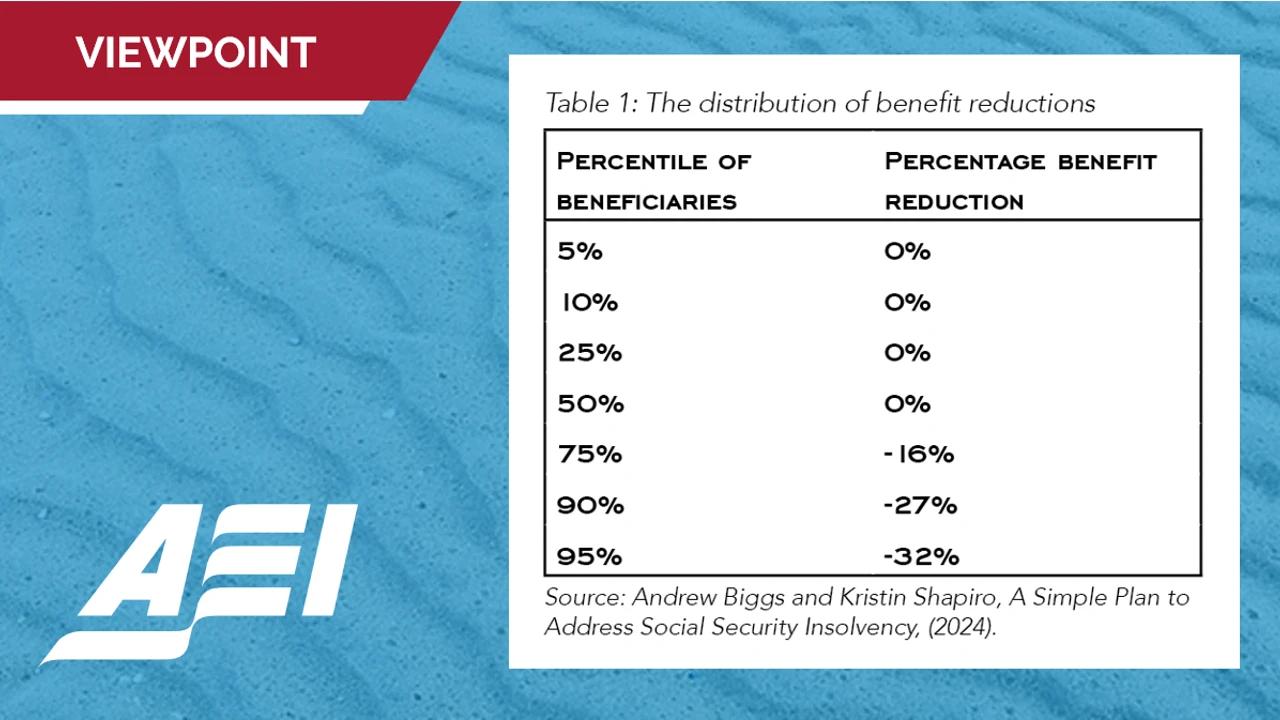

Social Security’s trust fund for old age benefits runs dry, the actuaries tell us, in 2033. Thereafter, only enough money will enter the system to pay 79% of benefits earned under today’s calculations. American Enterprise Institute scholar Andrew Biggs has done a bit of careful reading. Believe it or not, Social Security is not the first instance where the Congress has promised benefits to a class of citizens without sufficient appropriation. Biggs finds that, in the absence of enough funds from the legislature, the executive branch has wide latitude to administer cuts as they see fit, across-the-board cuts are not required. Biggs calculates that capping the individual benefit at $2,050 fixes the problem. This change means no benefit reduction for 50% of seniors and no beneficiary will be pushed into poverty by cuts.

But people in or nearing retirement have been contributing to the program based upon a very specific formula for calculating benefit levels. They have been doing so for decades. A worker now 64, who has been contributing at the maximum level for her entire adult life has paid in (including the employer contribution) about $450,000 at full retirement age of 67. At a capped benefit, this worker will get all of her money back (with zero return), 18 years into receiving benefits – age 85!

Remember the basic structure under current law. Your Primary Insurance Amount (PIA), is based on your earnings in your 35 strongest years. But the calculation is not linear; you get 90% of the first $1,057 of monthly earnings, 32% of the next $5,904 of earnings, and 15% of the earnings above that, up to the maximum. Capping the monthly benefit at $2,050 effectively means you get 90% of the first $1,057, 32% of the next $3,104, and a goose egg on all earnings above that, almost completely upending the linkage between taxes paid and benefits earned. Today’s structure is already highly progressive. In addition to the “bend points” (described above), the return on earnings beyond the top 35 years is zero, benefits are taxed for high earning seniors, and incremental Medicare Part B premiums for highest earning seniors under IRMAA means that 35% or more of your diminished Social Security benefit will be clawed back by the government before you ever receive it.

Andrew Biggs is a smart guy. He has seen decades of legislative inaction in the face of impending insolvency. Public understanding of the discretion available to the Executive might force the people and the Congress to get serious about reform. The soothing assumption today is that 2033’s insolvency means a 21% across-the-board cut that would push millions of seniors into poverty. Because that is unthinkable, Congress will find some way to supplement benefits with appropriated funds. A middle way seems possible, but it is a middle way that cuts benefits for the wealthiest, best educated, and most politically active seniors. But if the Executive branch can make these changes unilaterally, perhaps the Congress will get serious about some practical changes before our national Camaro hits the bridge abutment.

What can wealthy seniors do about this? People approaching Full Retirement Age might consider taking benefits at that date rather than maximizing benefits by waiting until age 70. At least you’d get your “current law” benefit for a few years before the cuts. Other than that, political action seems appropriate. Cutting Social Security benefits by 27% and more for the 10% of seniors who have paid in the most – that might generate some calls to Congress.